Ariana Connor, Skylar Locke, and Tai White

Stories Matter

Definitions:

The Oxford English Dictionary provides us with multiple, complex and often, differing definitions of “story.” One way a story can be defined as “an oral or written narrative account of events that occurred or are believed to have occurred in the past; a narrative account accepted as true by virtue of great age or long tradition” (OED). There are a plethora of ways in which one can interpret a story and the ways in which it is told. A more unconventional perspective of a story is “an event, statement, or situation that supposedly epitomizes one’s life or experience. Frequently in that’s the story of my life and variants, used as a resigned acknowledgment that one has experienced a particular misfortune too often” (OED). Another way of defining a story is “a narrative of imaginary or (less commonly) real events composed for the entertainment of the listener or reader; a (short) work of fiction; a tale” (OED).

Etymology:

< Anglo-Norman storie (early 12th cent.; also estorie , istorie ), variant of Anglo-Norman and Old French estoire tale, narrative, history, account, source, text, etc.

Keyword in Action:

We are quick to fall victim to what Chimamanda Adichie portrays in her TED talk as “the danger of a single story.” According to Adichie, the danger of a single story is “[showing] a [person] as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.” People have a tendency to only take a single idea, message, or lesson from a story and that becomes the entire story. This is problematic because storytelling allows us to make meaning out of the chaos of human existence and, in turn, understand who we are as individuals. If we only take single ideas out of stories then, we limit ourselves to one single perspective and definition. Through analyzing Zong! By M. NourbeSe Philip, The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of A Girlhood Among Ghosts by Maxine Hong Kingston, and Mean by Myriam Gurba, we can see how influential stories are and how beneficial it is to view stories in an open-minded and creative lens rather than from a single, limited perspective.

In Zong!, M. NourbeSe Philip creates found poems by retracing the horrific events that took place on the slave ship to Jamaica in November 1781. She turns the law document of the Gregson v. Gilbert case that views the event through a biased, restricted perspective into chaotic, confusing found poems. Approximately 132 enslaved Africans were killed in the Zong Massacre and were unjustifiably and intentionally chained together. They were then, thrown overboard by the captain due to illnesses from a shortage in water and food supply. The law document of the Zong Massacre gives a one-sided story from the court’s side of view rather than the stories from the victims. Philip’s found poems are the voices of the enslaved Africans that never had the chance to tell their story.

Philip’s poems epitomize the horrors of the Zong Massacre and recover history by challenging the readers to create a story from the unsaid accounts of the enslaved people. She forces the readers to interpret stories in a new, unconventional way. There are multiple different ways in which one can read and understand the found poems in Zong! The abstractness of these poems forces the reader to imagine the outcomes of the massacre and attempt to piece together the events that occurred that day.

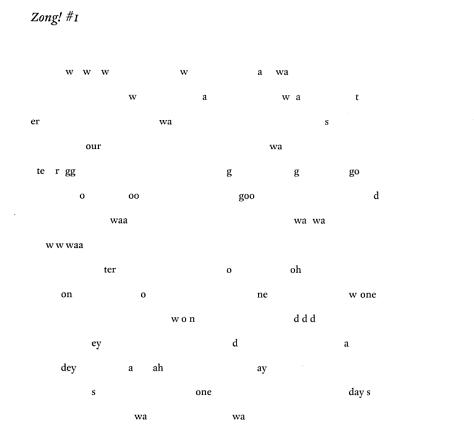

Photo from Zong! On page 3-4

The first found poem in Zong! is complicated to read because the design goes against the ways that stories are formally structured; however, this is ultimately Philip’s goal. She is placing the responsibility on the reader to recreate the story of the Zong Massacre. The words one can easily pick out in the poem are “water,” “god,” “days,” “one,” and “won.” The overuse of the letter “w” and the word “water” are used to reflect the surroundings of the enslaved people. Whereas, the letter “d” and the use of the word “days” represents how long these enslaved people were held captive. Philip effectively scatters these letters to show the mess of the massacre that took place. Zong! brings light to this massacre.

Philip changes the original, unjust court document and takes specific words from it to express the turmoil under the massacre. The senselessness of these words further represents how foolish the captains on Zong were and the leaders in the court case. The law document from the Gregson v. Gilbert court case broke down the Zong massacre into a rational and simple event. If we compare the formatting of her found poems to traditional stories that are formally written and easier to digest then, we are able to open our minds to the different ways a story can be told. Stories are effective and are used in ways to separate the readers from the outside world and put them in a time warp to alter the ways they treat and read stories.

In Maxine Hong Kingston’s novel, The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of A Girlhood Among Ghosts, single stories shape the narrator’s life and restrict her from finding her individuality as a young Chinese-American girl. The narrator rejects single stories which allow her to enter the world of multiple, creative stories. Storytelling allows the narrator to liberate herself from being stuck between the norms and identities of being both Chinese and American.

Kingston’s novel, a memoir (the story of one’s life) ironically, opens with the story of someone else. By opening the memoir in this intriguing and strange way, Kingston suggests that stories do not have to follow the traditional layout of what a story is. With that, her novel begins with the narrator reimagining the single story of her dead aunt, the No Name Woman. She creates three imaginative stories about her aunt to understand her evolving womanhood. In the first version, the aunt was raped by a man. In the second version, the aunt chooses to have sex with a man, leading to her pregnancy. In the final version, her aunt sleeps with a man because she was a “wild woman” (Kingston 8). The intention of this story is to create fear in the narrator and portray the danger of sexuality. The mother threatens her daughter by stating “what happened to her could happen to you. Don’t humiliate us. You wouldn’t like to be forgotten as if you had never been born” (Kingston 5). As a result of this story, the narrator becomes traumatized and is fearful of men. She states “as if it came from an atavism deeper than fear, I used to add “brother” silently to boy’s names” to make them “less scary” (Kingston 12). By listening to her mother’s story of her aunt, the narrator is restricted from the ability to explore her curiosity in romantic relationships and boys.

The narrator does not take the story as a cautionary tale that was intended to restrict her life possibilities; instead, she turns it into a story that expands on them. In the narrator’s stories of her aunt, she gives the No Name Woman freedom to be in control of her situation. However, the aunt was not allowed to have this type of freedom due to the strictness of Chinese culture. The narrator desires to break away from the roles given to her in Chinese cultures such as being a “wife” and a “slave” (Kingston 10). She refuses to let a single story restrict her role as a woman and more broadly speaking, as a person. With that, she creates multiple, imaginative stories that aid in her search for her identity. Kingston pushes against this idea that stories only come in one exact form with a single purpose. She wants us to understand that stories exist in many, different versions and perspectives and are allowed to be flexible in the eyes of the storyteller and listener.

Myriam Gurba’s Mean, a memoir of violence and dark humor, pushes against the traditional way a memoir is written by opening with Sophia Torres’ story, not her own life story. By doing this, Gurba is telling the world a story that would have never been taught or given the proper attention it deserved. She is portraying that a “story” has the power to bring awareness to stories that go unnoticed.

Throughout the majority of the book, Gurba writes stories that are focused on the sexual assault and death of Sophia and how Gurba feels emotionally guilty by this event. We do not find the exact reasoning behind her guilt until the end of the book. Gurba states “the man [who] . . . sexually [assaulted] me murdered Sophia Torres” (112). At this moment, we find out that Gurba was not only sexually assaulted but raped by the same man that raped and killed Sophia. In an interview with Gurba, she states “I carried around a lot of survivor guilt because I share a lot in common with the other victim that didn’t survive. But one of the things we don’t share in common is survival” (Racho). Gurba struggled for so long with the death of Sophia because she could have as easily been the victim that died; she was unable to come to an acceptance that she survived. At the end of the book, Gurba allows the ghost of Sophia to live within her and experience life through her.

If it was not for Gurba, many people would be completely unaware of who Sophia was and what happened to her. In the interview, she states “in some ways I wanted to make her somebody, at least in death” (Racho). Sophia’s story was viewed as one that did not matter and went unnoticed. However, Gurba uses her book to show that her story matters. She intentionally waits until the end to reveal that the story is not only Sophia’s but also her own. Through her book, she effectively to shows how a story is not only a single story.

As Adichie states at the end of her TED talk, “when we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise” (TED). Stories matter and are influential in everyone’s life. They fill our society and in order for us to grow, we must not limit stories to one single definition and generally speaking, single stories. Stories are important because they provide us with the opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of our experiences and who we are as individuals. If we reject single stories, then we are able to enter a creative realm where stories fly around with different messages and ideas.

Works Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda. “The Danger of a Single Story”. TED, July 2009.

“Discover the Story of EnglishMore than 600,000 Words, over a Thousand Years.” Home: Oxford English Dictionary, www.oed.com/view/Entry/190981?rskey=K2BqaW&result=2#eid.

Gurba, Myriam. Mean. Coffee House Press, 2017.

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of A Girlhood Among Ghosts. Vintage International, 1976.

Philip, Marlene Nourbese. Zong! as Told to the Author by Setaey Adamu Boateng. Wesleyan Univ. Press, 2008.

Racho, Suzie. “Myriam Gurba’s ‘Mean’: A Memoir of Hurt and Humor.” KQED, 28 Feb. 2018, www.kqed.org/news/11652366/myriam-gurbas-mean-a-memoir-of-hurt-and-humor.

“Story | Search Online Etymology Dictionary.” Index, www.etymonline.com/search?q=story.