We have already talked about the importance of the content and the way Claudia Rankine develops her own story in her own way, making the reader feel involved in the situations she is depicting. Citizen: An American Lyric, as we know, is divided in different parts that differ from one another in the way they are written: sometimes paragraphs that portray different racism acts, sometimes stories that require more explanation, as for instance, the Serena Williams’ one…

Today I would love to go a little bit further and get a bit deeper in the meaning and transcendentalism of the book by analyzing the different images she is using and the different connections we need to understand by the language she is using.

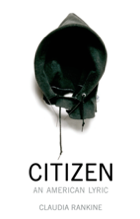

I will start by the very beginning, the cover of the book:

The purpose of Rankine’s “lyric” is to address how prevalent racism is and how we all participate in this. She wants us, the readers, to understand and feel uncomfortably aware of every single act of discrimination, to read what she has to say in two ways: as the victim, and as the oppressor. She tries, and success, with every little detail.

The cover is the first part of a book we encounter… what does this imply? In an interview with The Believer, the interviewer states he associates the image with slavery, Rankine then explains “it’s a hoodie that the conceptual artist David Hammons made in 1993, two years after the Rodney King beating”, who was a survivor of an act of police brutality. Then the author talks about the murderer of Trayvon Martin, a 17 year old student that was shot in 2012, she claims that “the sense that he brought on his own death by dressing like a hood, made many believe Hammons made the piece in response to his murder. But Hammons knew or knows already.” Let’s focus on these last words. Rankine wants the reader to understand that racism and racist acts transcend beyond time and space, and, as she presents along her work, are still present today.

As we read the first pages, we find the quote “If they don’t see happiness in the picture, at least they’ll see the black” found in a documentary by Chris Marker that deals with issues of the nature of human memory and how personal and global histories affect us. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HBYY9LSxylw) When I was rereading the book for the second time, it caught my attention the similarity of this passage and the one in page 46: “Obviously this unsmiling image of you makes him uncomfortable, and he [, the friend she is addressing] needs you to account for that.” (Rankine) This made me think of the relevance of that first line, as the incompatibility of happiness and being black is stated, and will be proved though the book.

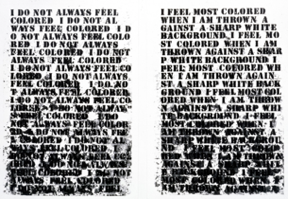

Images continue being a crucial part of this book, and this section we find only three, but I will address two:

These two images have a double duty, first of all, they make the reader feel uncomfortable and uncertain of what is going on as we don’t really understand the meaning of the second one or why the first one is written the way it is written and what she wants us to get from the message. And also, by using these images, Rankine wants us to realize the importance of the contrast of colors, as they are the first pictures in black and white that we find in the book; the first one presenting a text written in black on a white background that slowly degenerates and stars being unreadable but that presents a pattern of two sentences that reads “I do not always feel colored… I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” This message makes us pay attention to a black text in a white background in an ironic way, since all the book is written in the same way: black typing on white pages; but she wants us to pay attention specifically to this one image, and she wants us to realize how the letter start to fade. On the other hand, the second image is challenging this, the common thought of a white background and black images on it, as it is presented the other way round.

I would also like to address the different connections the author has been using with language through this section, she continues paying attention to Serena Williams’ story, but this time she wants the reader to feel what she is feeling, Rankine is comparing the feelings and frustration of the tennis match Williams lives with feelings in reality, a daily fight: a match that transcends; as we see in these examples: “The ball isn’t being returned. Someone is approaching the umpire. Someone is upset now.” (Rankine 64), “though you can retire with an injury, you can’t walk away because you feel bad”. (Rankine 65)

I also find very interesting the way Rankine talks about headaches in a figurative way. In page 61 we find out “the headaches begin” (Rankine), in page 62, “the headaches remain” (Rankine), and, finally, in page 69 “despite everything, the body remains” (Rankine)… she is addressing how tiring the daily fight gets, how these “headaches”, this pain, begin… and remain; but, in spite of the pain and the memory, the body remains, she stands still, and so does every victim of discrimination.

I have been paying attention to the imagery and pictures of this section, and my question is, do you think the images play such an important role? How do you think they work in the context of the whole book? Do the images break the ideas or the feelings you have while reading the text… or do they intensify them? And also, during this months, we have been addressing the importance of storytelling and having a voice, Rankine is aware of it as she indicates in page 61 when she compares narrative to creating lives. How do you think she is employing the act of telling stories? Do you think her method is effective? Why (or why not)?

Bonus:

Here is the link to Rankine’s website just in case you want to learn a bit more: http://claudiarankine.com/

Bonus (II):

I found this caricature of Serena Williams and I just wanted to leave it here and see what you all think

Works Cited:

Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf Press, 2014.

The Believer interview: https://believermag.com/logger/2014-12-10-i-am-invested-in-keeping-present-the-forgotten/